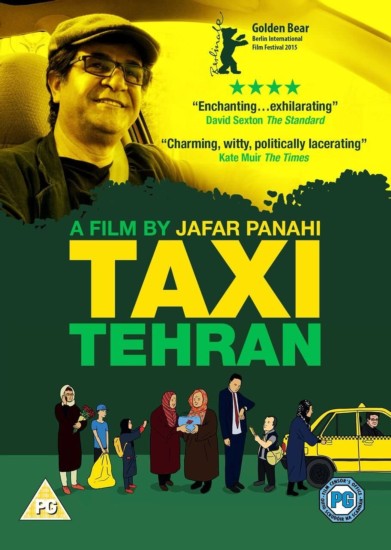

Taxi Tehran

Jafar Panahi, the director, has been jailed and given a 20 year ban on making films by the Iranian government - so what does he do? He poses as a taxi driver and makes a film about the passengers he drives through the streets of Tehran.

Film Notes

BERLIN 2015: ‘TAXI’ REVIEW.

A major work from Jafar Panahi screens in competition at the Berlin Film Festival as again the Iranian director challenges the ban on filmmaking set on him by the regime’s authorities. Taxi (2015) is the director’s third film since, and it’s brighter and funnier than his moody This is Not a Film (2011), breezing along as it does through the streets of Tehran with Panahi disguised – not too well it must be said – as an on-the-beat cab driver. Its heart beats to a complex rhythm in which, unable to officially direct (the film comes without credits), Panahi films documentary-style with a camera strapped to his dashboard, shipping various members of Tehran’s community across town.

He’s a cheeky presence, smiling wryly, barely knowing his way around the city. He picks up teachers and old women going about their business, but also dissidents and in one scene an injured and bloodied man. This being Panahi, could he be a protester? But Taxi isn’t that abrupt. Instead he’s a victim of a motorcycle crash, who’s more hypochondriac than medical emergency. Most disarming about Panahi’s viewpoint is how deftly he succeeds in shifting gears from light comedy to serious national issues. One conversation with a lawyer – like the filmmaker, banned from her profession – goes from family small-talk to hunger strikes. It’s part of the director’s self-aware confidence that the hunger striker is a woman who tried to go to a volleyball game – imitating the plot of his 2006 film Offside.

Indeed the taxi itself is a reference to Abbas Kiarostami’s Ten (2002) which is set entirely inside a cab and was featured recently in Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s Tales (2014). That freewheeling spirit grips the film. When a pirate DVD salesman hops into the car, the director offers a knowing smile when he’s recognised. Wishing to justify his profession, the pirate asks “how else can students see foreign movies?” Last time they met, Panahi rented Midnight in Paris (2011) – what an unnatural thing to imagine him watching that. Sure, it’s contrived, but Panahi’s gaze is unobtrusive, its profundity accidental. Here is the director stuck in a taxi (not house arrest, as previously), a claustrophobic space perhaps, and yet the film is visually lively, the conceit brilliantly made out. At 82 minutes, this is a brisk but hugely powerful work that is cinema of the oppressed par excellence. The conclusion comes when he picks up his niece from school, when it’s established she has to make a “distributable” film for a school project. It’s one in which the heroes have to have names of Islamic saints, where women where headscarves and which can’t show any “sordid realism”.

It’s a ridiculous set up (how many Tehrani schoolkids would have cameras?) but Panahi’s blabbermouth wannabe filmmaker relation is an energising presence. According to her teacher, the film “can be real” but not “real real”. So when she films a kid pick up money dropped by a passer by, she tells him to give it back so she can use it in her film. It’s a clever proposition about the nature of film directing – it controls, it contrives, as much as it documents. Of course, that’s not what real life is like; he can’t give it back, so she can’t use her film. That’s all that Iran allows. But it’s not just referencing Panahi’s situation. Not acknowledging – indeed not recording – reality as it is for people is how oppressive regimes thrive. “We have to get to the root of the problem” poses one passenger early in the film. As raised by all of Panahi’s work, that root is just what is so difficult to change. Never is the panoply of Tehran culture more succinctly put than in this masterful film.

Ed Frankl, Cine Vue,

On paper, it looks like yet another Jafar Panahi exercise, outsmarting once again the Iranian authorities who have forbidden him from making films for the next 20 years. On screen, however, this is a delightful surprise, and though it is even more minimalistic than his last two illegal exports, This Is Not A film and Closed Curtains, it is also more mature, and better calibrated and - at the risk of annoying art house patrons who often hate this term - more entertaining than the other two.

More than ever before, Panahi’s composite picture of contemporary Iranian reality puts on a satirical shape, but the melancholy smile on the driver’s face – and in this case driver and director are one and the same person – is more eloquent than any piece of dialogue.

Following in the footsteps of 10 by Abbas Kiarostami (whose assistant he used to be), Panahi’s new film is shot entirely inside a yellow cab travelling through Teheran, with two revolving digital cameras fixed on the dashboard, pointed most of the time inside the car but occasionally turned around to look at the street, but never leaving the confines of the vehicle.

As biting, dark and existential as Kiarostami’s opus was, but disguised under a lightweight almost flippant disposition, the entire film is built around Panahi, who drives the cab himself, mostly listening to his passengers as he crosses Teheran from one end to another. In the process, he offers a priceless cinematic lesson, proving once again that if you know what you want and how to express it, the whole mystical paraphernalia of filmmaking and its inflated budgets is not really necessary.

In a series of apparently unrelated vignettes, Panahi’s customers come in and leave the taxi, arguing about anything from the ease of dispensing capital punishment in Iran to the flourishing black market in illegal videos. Naked greed is revealed at one point and deep human compassion at another; a little girl is introduced as the driver’s niece and shamelessly steals every scene she is in with her sharp wits and even sharper tongue; a conversation about the physiognomy of delinquents leads to the conclusion that they look like everybody else and a set of definitions for correct Islamic filmmaking is dictated by a teacher to the niece for her school assignment. And though this sounds like a parody, it is perfectly authentic and Panahi himself has been condemned for not respecting it.

A civil law lawyer disbarred for her activities goes around with a smile on her face distributing flowers to her former clients; references galore are made to films in general and to Panahi’s films in particular, while he keeps on driving the car, using a finger to push the camera on the dashboard one way or another, just to remind the audience they’re watching a film and there is a director deciding what the camera is supposed to see. Brisk editing could suggest a flimsy approach to each of the many subjects raised, but the script puts them across so adroitly that no target is missed all through.

More than ever before, Panahi’s composite picture of contemporary Iranian reality puts on a satirical shape, but the melancholy smile on the driver’s face – and in this case driver and director are one and the same person – is more eloquent than any piece of dialogue. How this film was made, cut and put together; how it was sneaked out of Teheran and how come the regime there is not blowing a fuse are questions that remain to be answered. The film, however, stands on its own merits. And if you’re wondering about the missing credits, Panahi prefers not to quote any other names beside his own. No need to explain.

DAN FAINARU, Screen Daily, 6 FEBRUARY 2015.

What you thought about Taxi Tehran

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 (45%) | 10 (50%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 20 Film Score (0-5): 4.40 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

70 members logged in to view the short film Bring Roberto and Taxi Tehran.

The votes cast has made Taxi the most popular film of the season so far with a score of 4.40.

All comments received are below.

"As with many of his other films, Panahi's Tehran Taxi challenges class, gender and ethnicity inequalities in Iran; not surprised he's been banned from making films, travelling abroad and likely to be locked up. This is part of a genre of driving movies in Iran, as was 'Ten' in 2002. Original, satirical and imaginative, did think some of the fares may be set up and semi-scripted yet this adds to the and anecdotal playfulness of the film. Informal dialogue and filming style, makes the viewer feels s/he in on a literal cinematic journey

Liked the debate about the death penalty, especially as the man is a mugger! Then the man selling banned foreign films reflects the popularity, albeit unofficial, of film, music and art. The shock of the fly-on-the-wall piece of a motorcycle accident victim who gives his will leaving his house to his wife rather than his brothers as would be expected in Iranian society so that she gets her fair share." Giggled a lot at the goldfish pair and the smashed bowl; fish are saved a weird depiction of superstition. Women get into another taxi as Panahi has to pick up his wonderfully 'gobby' niece who starts a film-within-a-film with the young girl making a movie who has learnt how to make officially distributable films. She knows exactly what to do to get round the rules and regulations to tell her story.

A wonderful conversation with the flower woman who tells of a young prisoner on hunger strike; most overtly political part of the film, most daring given Panahi's position as out of favour in Iran. Taxi Tehran is a powerful resonance to the power of film as a medium for protest, advocating for its use as a way of conveying interactions and emotions – and giving us a good chuckle."

"A glance at the director/actor's face is all you really need to know - warm, gentle, amused and quizzical. A driver who doesn't know where he's going and appears not very greatly to care. A film, other than being about current Iranian reality, that is principally concerned with storytelling and film making. It comes from the opposite direction from what you'd expect ('La suit Americain' for example) it is apparently cinema verité but gradually one queries the convenience of some dialogues and so we begin to feel somewhat unmoored and drifting unable to tell what is real and what is not and to what degree we're being manipulated. In this world it doesn't hurt to be reminded to question what you're being told".

"Nice camera connection between the short and the non-distributable film. Liked the non dramatic realism of the first and loved the utter unpredictability of the second. Jafar and his niece in particular were wonderful and his conversations with his passengers were all memorable, especially with his old neighbour on finding out what a thief looks like and with the flower selling lawyer and living in a repressive censored society. A noble film."

"Beautifully subtle"

"Such a fascinating and subversive vehicle for getting the views of what is really going on in the country. Loved his niece and the lawyer - very clever and watchable film. An admirable piece of cinema under extreme conditions".

"Being Roberto was a great short film. Very good production values, nuanced performance by the lead actor, a storyline which most of us have experienced in some form (leaving home, spreading our wings, pursuing a dream yet torn by love and a sense of responsibility to our parents). Very well done!"