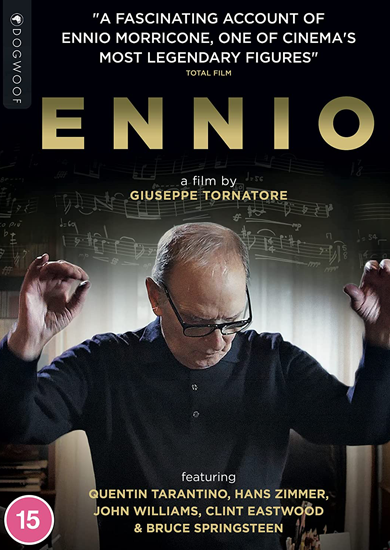

Ennio

A portrait of one of the most prolific film composers of the 20th century, this celebrates the life and legacy of Ennio Morricone. A nostalgic trip through some of the most well-known film themes ever made.

Film Notes

Ennio review – Giuseppe Tornatore’s heartfelt tribute to film composer Morricone.

The maestro talks about what drove his famous scores while actors, directors and musical peers celebrate his contribution to cinema.

This documentary represents a painstakingly detailed, fantastically entertaining, and profoundly exhausting deep dive into the career of the hyper-prolific Italian composer Ennio Morricone, known best perhaps for his orchestral scores for Sergio Leone (including the so-called Dollars Trilogy and Once Upon a Time in the West), Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers, Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1900 – and a whole bunch of American films, ranging from the great (Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables) to the abominable (Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight).

It’s not so much the running time of 156 minutes that will tire you out as the incredible sonic, visual and emotional overload generated by the work itself; perhaps this is ideally seen first in a cinema for maximum impact and then again in small, digestible chunks at home. It’s one huge cinematic mosaic that tessellates a massive interview with the man himself (fortuitously filmed just before he died in 2020) with acres of archival footage and snippets from the movies he wrote soundtracks for.

On top of that, there’s hundreds of interview clips from his innumerable collaborators, friends and admirers – even if some of them seem to be there just to show off how good the producers were at snagging big names. (Bruce Springsteen, for example, is a bit too gushy and hyperbolic.) However, any weak spots are more than compensated for by the overall level of discourse that gives paramount place to the music above all else, with intelligent, pithy observations from Morricone’s classical composer contemporaries such as Boris Porena, as well as other film music maestros including Hans Zimmer and Mychael Danna.

As you would expect, there are lots of lovely personal anecdotes from assorted collaborators, including Joan Baez and singers little known outside of Italy who remember Morricone’s innovative arrangements for RCA pop songs before he moved into film. English director Roland Joffé is particularly entertaining, showing off his Italian while discussing Morricone’s mighty score for Joffé’s The Mission, which we see performed by a massive orchestra with Morricone conducting. Given the documentary’s director is Giuseppe Tornatore, it’s no surprise a small chunk is given over to his collaborations with Morricone such as Cinema Paradiso, but on the whole Tornatore makes it ultimately about his main subject. Kudos is also due to editor Massimo Quaglia’s astonishingly fluid work splicing it all together.

Leslie Felperin, The Guardian, 20th April 2022.

‘Ennio’: Film Review | Venice 2021

Filmmaker Giuseppe Tornatore assesses the career of his late collaborator, the renowned movie composer Ennio Morricone.

Of all the filmmakers who owe debts to the great Ennio Morricone, surely few owe as much as Giuseppe Tornatore: 1988’s Cinema Paradiso was a crowd-pleaser for many reasons, but would’ve had a harder time becoming a global hit without Morricone’s romantic, nostalgic score. Tornatore worked with the composer many times after that first collaboration, and is well positioned to offer the career-capping Ennio, which arrives barely a year after Morricone’s death.

Happily, the film is more than a greatest-hits rundown (and at nearly three hours, it had better be): In addition to nuts-and-bolts musicology, it offers real engagement with a complicated character, endearingly stubborn and self-effacing, whose inventiveness changed both his chosen field (“absolute” music) and the one, film scoring, he entered only reluctantly.

The maestro sits onscreen for much of the film, alert behind his giant spectacles, telling stories about a career he’d intended to be entirely different — even after he gave up a boyhood ambition to be a doctor. (His father, a professional trumpeter, insisted that little Ennio should follow the same path.)

Morricone recalls the humiliation of playing for food during the occupation of Italy in World War II. His play-for-peanuts experiences may have left a visible mark, because when he entered a program to study composition, the young man was at first allowed to write only dance tunes. Morricone craved the approval of his mentor, the composer and teacher Goffredo Petrassi — he still remembers the grades he got on assignments — and he did make headway in the academic arena, eventually helping to form an avant-garde collective inspired by John Cage.

But he was always doing commercial work as well, staying up all night to crank out arrangements for TV shows that didn’t credit him by name. This led to arrangements for pop singers, and Tornatore shows us many enjoyable examples of what Morricone’s contemporaries are describing in interviews: Where previous arrangers simply wrote orchestral parts to follow a song’s chords, he was inventing something new, giving the orchestras much more to do, and adding elements no pop producer at the time would have imagined using, from tin cans to typewriters.

The film’s brief but delightful tour through these bing-bongy pop tunes, enriched by interviews with Italian stars like Gianni Morandi, suggests that a very enjoyable film (if one appealing to a more narrow audience) could be made on these years alone. But that’s not why we’re here, of course. It’s time to start whistling.

Morricone composed scores for two Westerns under a pseudonym, not wanting to be associated with the genre, before teaming up with Sergio Leone. (The two were surprised to realize they’d been classmates in elementary school.) The director took him to a Kurosawa picture to explain what he had in mind, and the rest is spaghetti.

The doc’s look at A Fistful of Dollars is the first of several places in which Morricone explains how he borrowed from his own work, repurposing an arrangement he’d done for a country song. His work on that movie is also a key example of his putting his foot down — though not the first, as we’ve already heard how he swore he’d quit his conservatory if they didn’t let him study under Petrassi. When Leone intended to use a Degüello from another movie in a key showdown scene, Morricone was so offended he threatened to quit. Leone backed down.

Morricone would lose some artistic conflicts, but it seems they were often occasions on which he underrated his own work. When he sent Brian De Palma nine ideas for a victory theme in The Untouchables, he told the director, “Please don’t choose number six.” But number six is in the movie, and it’s hard to imagine any music that would serve the scene better. He also initially refused to write music for The Mission, claiming that Roland Joffé’s images were so beautiful he could only make things worse. (Again, Ennio: Wrong.)

But for serious self-deprecation, you have to hear Morricone claim that he “hates melody.” Other composers interviewed here (tons of them, in the film world and outside it) are astonished at this idea, coming from someone who has created so many memorable melodies. But there are only so many ways tones can be ordered, and Morricone calmly says, “I think that we are out of melodic combinations.” Good thing he had so many other compositional tools to work with.

As the film chronicles his increasing success and gathers awestruck observations from admirers (among them Bernardo Bertolucci, Pat Metheny, Hans Zimmer and Bruce Springsteen), we hear both general music-theory talk and a surprising number of specific anecdotes — how a chanted protest in the streets influenced a score; how he worked the letters B-A-C-H into another. For film buffs, there are enjoyable stories about his working experiences with Terrence Malick, Oliver Stone, Dario Argento — but not, sadly, with Stanley Kubrick, who wanted Morricone to score A Clockwork Orange. Evidently Leone torpedoed that by lying to Kubrick; it was the only job Morricone regretted not getting, he says.

There’s so much to enjoy here that we’re far beyond the two-hour mark when a viewer starts to observe things he might be willing to do without. We could easily have gotten by with half as many scenes of Morricone on tour, conducting his most famous work for rock-star-size audiences. Perhaps we don’t need so much horrific archival footage to remind us what inspired his “Voices From the Silence,“ a reflection on the Sept. 11 attacks. And while we’re in a tweaking mood, can we do something about the sloppy subtitles, which sometimes flub even English-to-English transcription and misspell more than one household name? (Though they’re at least consistent on that front, with multiple references to some director named “John Houston.”)

But none of the above diminishes the pleasure of spending time with a man who kept working at the highest level to the end, finally winning the Oscar he coveted (for The Hateful Eight) when he was pushing 90. Ennio leaves one wanting to rewatch dozens of movies, dig up more for the first time, and scour the internet for Italian pop records that may never have been released on these shores. Thank goodness Mario Morricone talked his son out of going to med school.

John DeFore, The Hollywood Reporter, 17th September 2021.

What you thought about Ennio

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 (54%) | 8 (31%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 26 Film Score (0-5): 4.31 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

75 members and guests attended the screening of Ennio. There were 26 responses which is a 29% response rate.

Your collated responses are below.

“More than interesting as a biography, as an arts documentary, this one does a job of explaining why Morricone is as close to a genius as possible. He gives us a warmly emotional presence on camera who never flags, more than can be said for the other tributes that become somewhat repetitive. The film's chronology obliges us to see everything Morricone ever did, rather highlighting achievements and building the film around those. The who's who of directors – Pontecorvo, Leone, de Palma, Bertolucci, Joffe – all seem awed by him and his music that created 'a parallel movie' or 'a world that wasn't quite on the screen'. Zimmer and Williams' sharp comments felt both professional and heartfelt: "you can always tell it's him from the first note". Tarantino's outburst to the Academy that Morricone can only be measured against Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert: so Morricone's response is 'to establish the truth of this, one would have to wait 200 years' seemed laconic. Liked Morricone's continuing point that writing film music wasn't the poor relation to music in the classical and academic tradition. Thanks for showing this!”

“Engrossing insight into Ennio Morricone's long career. He came across as a modest and lovely family man and composer. Lovely music. Too bad that the subtitles were often hard to read. Also did not agree with the showing of 9/11 images - mistake by the filmmaker as they were real images whereas all the other images were from films”.

“Thank you”. “Rather long but worth it”. “Too long. Very instructive on how film music is created”. “Too late finishing, too loud, too gory…needed interval”.

“Brilliant – wanted more”. “Wonderful, wonderful, wonderful”. An excellent film showing the infinite possibilities of creativity! Loved it”.

“Very long but very interesting and wonderful music”.

“Inspiring and moving -surprisingly”.

“An insight into the violence of Italian cinema!! A musical treat”.

“Interesting and informative”. “Extraordinary. Very enjoyable. Far too loud though”.

“Extraordinary. What a career. Perhaps a bit long”.

“Interval would have been welcome”. “Brilliant”.

“Interesting - but an interval would have been welcome”.

“Far too long, but interesting”. Interesting but too long”.