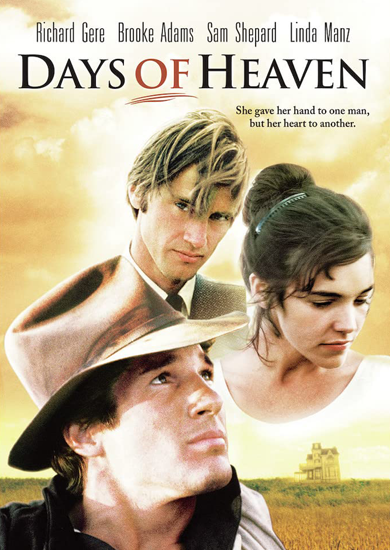

Days of Heaven

A farm labourer (Richard Gere) convinces the woman he loves (Brooke Adams) to marry their rich but dying boss (Sam Shephard) so that they can claim his fortune. Haunting and beautifully shot in the Midwest prarielands.

Film Notes

At the risk of being accused of repeating himself, Terrence Malick has here virtually reorchestrated (though with incomparably greater richness) the principal features of Badlands, using an oblique voice-off commentary to distantiate and lend poetic dimensions to the otherwise fairly banal story of young fugitives fleeing from the intolerable frustrations of society. Where Badlands was about the unilateral influences of untamed landscapes on two young urban delinquents, Days of Heaven widens its perspective to describe no less than mankind, the Earth, and their mutual interaction. Following and black-and-white montage of photographs summing up the legacy of industrial revolution, two images perfectly describe the totality if the urban inferno: outside, under a bleak sky, women drudge through a mountain of slag in quest of fragments of coal; inside, roasted by hellish flames, men toil like robots to keep the furnaces alive. Then, seen silhouetted against the skyline with people clinging to every inch of its surface, the train looms as a Noah’s ark heading for the promise of a new world, seemingly fulfilled as the paradise of the Texan wheatfields begin to stretch away, golden and lazily waving, as far as the eye can see.

“All three of us been going places, looking for things, searching for things, going on adventures”, Linda’s commentary had cheerfully started, almost immediately introducing a note of apocalypse as she describes the forebodings of a stranger on the train. “He told me the whole earth was going up in flames … There’s gonna be creatures running every which way, some of them burned, half their wings burning. People are gonna be screamin’ and hollerin’ for help…” Lush and pastoral, with herds of bison tranquilly grazing within reach of the harvesters, the Texan wheatfields seem to deny this vision as absurd.

Yet already the farmer’s stately mansion, perched in solitary splendour on the skyline in echo of Giant and apparently devoid of human inhabitants, looms as a House of Usher doomed to fall under the weight of human loneliness and folly. Already steam engines are rumbling in, shaking the earth as they hail in the machinery to make the harvesting easier, quicker, more profitable. Already the animals are cowering in fear as their domain is invaded. And as the harvest reaches its frenzied climax, one shot of a mechanical separator belching choking clouds of chaff and grain into the parched atmosphere is enough to signal the parallel (unnecessarily stressed by a flash cut-in) with the furnaces of Chicago.

This, one might say, is the thesis of the film, echoed by Bill’s Horatio Algerish rather than socialistic determination to wage his own war on poverty: “We got to do something about it; can’t expect anybody else to”.

At which point the film turns the thesis inside out in acknowledgement of the follies and frailties of the human heart. Unexpectedly, the phoney marriage turns into a true one; equally unexpectedly, the hungry intruders on wealth react with grace rather than with acquisitive greed; and against all odds, the quartet are forged momentarily into a tight family unit, imperfect only because the initial lie means that Bill can neither remain or bow out without destroying it. Almost achieved here, but disrupted from within, is the utopic balance that Linda reaches for in her attempt to explain Bill’s motivation: “He figured some people need more than they got, other people got more than they need”. Man, in other words, is turning in a vicious circle, destroying his earth in quest of the profit by which he is incapable of profiting.

The title of the film, given the extraordinary minatory power with which Malick invests his images of landscapes and objects – wind angrily ruffling a field of wheat, a scarecrow standing baleful guard by night, a glass preserving its taint of infidelity at the bottom of a river – seems to refer less to the numbered days of heaven enjoyed by the quartet on the farm, than to a time when gods once walked the earth where now only frail and fallible men persist in their illogical lives and unfathomable drives. Having destroyed their world, they are now dying along with it, purged from its face by the plagues of fire and locusts; and what is perhaps the key image in the film comes when, soon after embarking on his final flight, arriving at a river crossing, Bill is seen in enigmatic long shot holding out a medallion necklace to the ferryman. Obviously trading for a boat, he is also paying Charon prior to crossing the Styx; and as the boat pursues its ghostly voyage down the river, what we see are tranquil images of people going peacefully about their business, but what we hear is Linda’s attempt to explain these visions: “And you could see people on the shore, but it was far off and you couldn’t see what they were doing. They were probably callin’ for help or somethin’, or they were tryin’ to bury somebody or somethin’. Some sights that I saw was really spooky, that it gave me goose pimples, and that I felt like cold hands touchin’ the back of my neck and … it could be the dead comin’ for me or something.” Having conjured the old Eden on its last legs, its course of self-destruction hastened by the industrial revolution, Malick then leaves it to die on the battlefields of the First World War. After that a new world began, with new and hitherto undreamed of forms of self-annihilation…

Tom Milne, Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1979

‘Terrence Malick's "Days of Heaven'' has been praised for its painterly images and evocative score, but criticized for its muted emotions: Although passions erupt in a deadly love triangle, all the feelings are somehow held at arm's length. This observation is true enough, if you think only about the actions of the adults in the story. But watching this 1978 film again recently, I was struck more than ever with the conviction that this is the story of a teenage girl, told by her, and its subject is the way that hope and cheer have been beaten down in her heart. We do not feel the full passion of the adults because it is not her passion: It is seen at a distance, as a phenomenon, like the weather, or the plague of grasshoppers that signals the beginning of the end.

The film takes place during the years before World War I. Outside Chicago, Bill (Richard Gere) gets in a fight with a steel mill foreman and kills him. With his lover Abby (Brooke Adams) and his kid sister Linda (Linda Manz), he hops a train to Texas, where the harvest is in progress, and all three get jobs as laborers on the vast wheat field of a farmer (Sam Shepard). Bill tells everyone Abby is his sister, and gets in a fight with a field hand who suggests otherwise.

The farmer falls in love with Abby and asks her to stay after the harvest is over. Bill overhears a conversation between the farmer and a doctor, and learns that the farmer has perhaps a year to live. In a strategy familiar from "Wings Of The Dove," he suggests that Abby marry the farmer--and then, when he dies, he and Abby will at last have money enough to live happily. "He was tired of livin' like the rest of 'em, nosing around like a pig in a gutter,'' Linda confides on the soundtrack. But later she observes of the farmer: "Instead of getting sicker, he just stayed the same; the doctor must of give him some pills or something.''

The farmer sees Bill and Abby in tender moments together, feels that is not the way a brother and sister should behave and challenges Bill. Bill leaves, hitching a ride with an aerial circus that has descended out of the sky. Abby, the farmer and Linda live happily for a year, and then Bill returns at harvest time. All of the buried issues boil up to the surface again, against a backdrop of biblical misfortune: a plague of grasshoppers, fields in flame, murder, loss, exile.

"Days of Heaven'' is above all one of the most beautiful films ever made. Malick's purpose is not to tell a story of melodrama, but one of loss. His tone is elegiac. He evokes the loneliness and beauty of the limitless Texas prairie. In the first hour of the film there is scarcely a scene set indoors. The farm workers camp under the stars and work in the fields, and even the farmer is so besotted by the weather that he tinkers with wind instruments on the roof of his Gothic mansion.

The film places its humans in a large frame filled with natural details: the sky, rivers, fields, horses, pheasants, rabbits. Malick set many of its shots at the "golden hours'' near dawn and dusk, when shadows are muted and the sky is all the same tone. These images are underlined by the famous score of Ennio Morricone, who quotes Saint-Saens' "Carnival of the Animals.'' The music is wistful, filled with loss and regret: in mood, like "The Godfather" theme but not so lush and more remembered than experienced. Voices are often distant, and there is far-off thunder.

Against this backdrop, the story is told in a curious way. We do see key emotional moments between the three adult characters. (Bill advises Abby to take the farmer's offer. The farmer and Abby share moments together in which she realizes she is beginning to love him, and Bill and the farmer have their elliptical exchanges in which neither quite states the obvious.) But all of their words together, if summed up, do not equal the total of the words in the voiceover spoken so hauntingly by Linda Manz.

She was 16 when the film was made, playing younger, with a face that sometimes looks angular and plain, but at other times (especially in a shot where she is illuminated by firelight and surrounded by darkness) has a startling beauty. Her voice tells us everything we need to know about her character (and is so particular and unusual that we almost think it tells us about the actress, too). It is flat, resigned, emotionless, with some kind of quirky Eastern accent.

The whole story is told by her. But her words are not a narration so much as a parallel commentary, with asides and footnotes. We get the sense that she is speaking some years after the events have happened, trying to reconstruct these events that were seen through naive eyes. She is there in almost the first words of the film ("My brother used to tell everyone they were brother and sister,'' a statement that is more complex than it seems). And still there in the last words of the film, as she walks down the tracks with her new "best friend.'' She is there after the others are gone. She is the teller of the tale.

This child, we gather, has survived in hard times. She has armored herself. She is not surprised by the worst. Her voice sounds utterly authentic; it seems beyond performance. I remember seeing the film for the first time and being blind-sided by the power of a couple of sentences she speaks near the end. The three of them are in a boat on a river. Things have not worked out well. The days of heaven are over. She says: "You could see people on the shore, but it was far off and you couldn't see what they were doing. They were probably calling for help or something--or they were trying to bury somebody or something.''

That is the voice of the person who tells the story, and that it why "Days of Heaven'' is correct to present its romantic triangle obliquely, as if seen through an emotional filter. Children know that adults can be seized with sudden passions for one another, but children are concerned primarily with how these passions affect themselves: Am I more or less secure, more or less loved, because there has been this emotional realignment among the adults who form my world?

Since it was first released, "Days of Heaven'' has gathered legends to itself. Malick, now 53, made "Badlands" with newcomers Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen in 1973, made this film five years later and then disappeared from view. Because the film made such an impression, the fact of his disappearance took on mythic proportions. He was, one heard, living in Paris. Or San Francisco. Or Montana. Or Austin. He was dying. Or working on another film. Or on a novel, or a play. Right now Malick is back at work, with two projects, "The Thin Red Line" with Sean Penn, and "The Moviegoer,'' with Tim Robbins and Julia Roberts. Perhaps the mysteries will clear.

"Days of Heaven's'' great photography has also generated a mystery. The credit for cinematography goes to the Cuban Nestor Almendros, who won an Oscar for the film; "Days of Heaven'' established him in America, where he went on to great success. Then there is a small credit at the end: "Additional photography by Haskell Wexler.'' Wexler, too, is one of the greatest of all cinematographers. That credit has always rankled him, and he once sent me a letter in which he described sitting in a theater with a stopwatch to prove that more than half of the footage was shot by him. The reason he didn't get top billing is a story of personal and studio politics, but the fact remains that between them these two great cinematographers created a film whose look remains unmistakably in the memory.

What is the point of "Days of Heaven"--the payoff, the message? This is a movie made by a man who knew how something felt, and found a way to evoke it in us. That feeling is how a child feels when it lives precariously, and then is delivered into security and joy, and then has it all taken away again--and blinks away the tears and says it doesn't hurt.

Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun Times,

What you thought about Days of Heaven

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 (34%) | 20 (49%) | 6 (15%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 41 Film Score (0-5): 4.15 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

112 members and guests came to see Days of Heaven.

You surpassed yourselves this week. We had 41 responses delivering a 37% response rate. Still nowhere near the 45% response rate we had before the pandemic. If you can’t think of anything to write, just give it a score; or wait 24 hours and write something for the website.

Below are your collated responses.

“This is a curious one to know how to rate; a weak story freighted with classical and biblical weight and an overall sense of impending societal doom that the story struggles to support. Additionally, it looks stunning. Often the visuals seem to be working an awful lot harder than the script, there are many superb images; the house like a ship at sail on a sea of wheat, the locusts and subsequent apocalyptic fire. The players are adequate; a subdued Sam Shepard, the brightest the lively Linda Manz. Richard Gere seems to have stepped in from an entirely different film though, an eighties gangster movie perhaps. Far too pretty, his arrogant, slouching manner does not have the physical sense of a manual worker or farmhand at all. Overall, very much a curate's egg experience”.

“Bloomin' marvellous! Badlands remade! Liked how Malick lets things unfold patiently avoid a straightforward narrative convention so that the slowness of it suddenly jolts us with the locust/fire sequence; wonderful photography of that fire. Days of Heaven' with a title from Deuteronomy gives the threads of its plot, showing Bill's flight from a hellish Chicago factory from murder to another murder of Shephard; intertwined with the paradise of endless land and sky that, is engulfed in locusts and roaring flames. And Bill's sister, narrates this saga with references to God and Satan. Simple plot with inevitabilities that if you're on the road, that's where you stayed in the 1910s and '20s; Grapes of Wrath came to mind. Let's have more of Malick please”.

“Beautifully shot and well desiring of its cinematography awards. Some mesmerising performances, especially Abby and Linda. Richard Gere was so young! and kept his 1970s hairdo against the odds for 1916. The growing tensions were subtly portrayed and tragedy felt inevitable. I felt that the only fault was in the ending: I thought that Abby would have been implicated in Bill's crimes and denied the inheritance, although I hoped that her husband would survive against the odds and take her back with Linda once she was free of Bill's influence. Her abandonment of Linda felt out of character”.

“As promised the photography was wonderful. I found some scenes strangely short and somehow disconnected to the main story. Memorable, beautiful and thought provoking”.

“I come fresh to each film, and read about it afterwards, as I think that is a fairer test. In this case, advance reading would have made it less confusing Lovely images, although the fire scene was unconvincing, but otherwise not up to scratch in my view. Weak story line, and it was not clear initially who was doing the voiceover. The farming scenes were implausible in the extreme (a profitable harvest would not have been that inefficient in those days) and the mix of periods for the equipment, trains and planes didn't help. Continuity poor in places”.

“Terrence Malick has a unique style of filmmaking - the slowness, the clarity of images, the music and the stories he tells which are ever so slightly left-of-centre. Enjoyable”.

“Great film. Richard Gere bests two better placed attackers and sends them to their deaths. This is a stretch”.

“The cinematography was the star of the show - highly evocative. But I found the plot predictable and both dialogue and acting clunky”.

“This was beautifully filmed, with some superb images & scenes enhanced further by the music. I liked the narrator's voice throughout the film and I thought the ending was perfect. I was slightly disappointed by the characters. I found them a bit two dimensional & under developed…in comparison to the carefully crafted shots & images!”

“Simply stunning. A perfect film for a large screen”. “Beautiful photography + compelling acting”. “Amazing photography. Locusts, fire, waving corn, archaic farm vehicles…...”

“Fabulous cinematography. Can’t believe Richard Gere had such a baby face!!”

“Great cinematography and music. Good social commentary too”.

“Every shot was a work of art! A real insight into the hardships of working the land. Beautifully made… a gripping story”. “Excellent cinematography. Haunting music and the power of the human spirit”. “Amazing beautiful cinematography”.

“Stunning photography – a poem in a film”. “Spectacular to watch, too little to say”.

“Amazing cinematography”. “Loved the characterisations and scenery. Soundtrack excellent”. Parallel with ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’. Similar themes”.

“Excellent photography. Beautiful film. Surreal scenes! Bizarre story”.

“The mystery is still unfolding”. “Interesting story – history of prairies”.

“One of the most beautiful films ever made. But I had forgotten about the annoying voiceover”. “Great panoramic views and sunsets”.

“Fabulous photography which created the feeling you were there”.

“The story was not very strong. I would have preferred not to have the sub titles”.

“Editing was a bit iffy and story a bit vague”. “Reminded me of ‘Butch Cassidy’. Liked the fact there was limited dialogue”.

“Very Hardyesque. Wonderful photography”. “The photography was excellent”.

“Picturesque scenery…great music, but not convinced”.

“Good to look at – but lacked dialogue and true acting”.

“Slow and lacking narrative”.