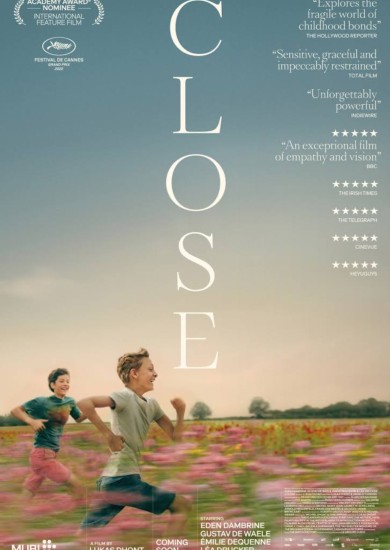

Close

Leo and Remi - 13 year old inseparable best friends – are tragically driven apart in this subtle study of childhood friendship and the end of innocence. Cannes Grand Jury Prize 2022.

Film Notes

Close review – a heartbreaking tale of boyhood friendship turned sour.

When two 13-year-olds are no longer close, the fallout is unbearably sad, in Lukas Dhont’s anguished second feature.

Belgian film-maker Lukas Dhont found praise and then a backlash of criticism in 2018 for his debut feature, Girl, the story of a young transgender woman auditioning for ballet school, which some found to be inauthentic, and an unwarranted fetishisation of a trans person’s body. It could well be that he will get more criticism for this new film on the grounds that the unselfconscious love and friendship between two 13-year-old boys is being catastrophised and problematised.

I admit there are times when Dhont goes straight for the deafening minor chords of anguish. But there are two excellent performances from newcomers Gustav De Waele and Eden Dambrine as Rémi and Léo, and also valuable appearances from the actors playing their mothers: Sophie (Émilie Dequenne – iconic for the lead in the Dardennes’ 1999 Palme winner Rosetta, when she was hardly older than the boys are now) and Nathalie (Léa Drucker). Rémi and Léo are inseparable, hanging out and playing together all the time: physical, tactile, joyful and innocent, but certainly far more intense than most 13-year-old friends. Léo is especially close to Rémi’s mum and is physically at ease with her. He particularly admires Rémi’s musical talent – he plays the oboe. Schoolmates suddenly become aware of the intensity of their friendship. Girls – who are perhaps honest, or perhaps malicious, or just somewhere between the two – ask Léo if he and Rémi are a couple. With malign, ersatz sophistication, they ask if Léo even “realises” it.

Soon the boys are starting to make mean remarks to Léo, who is angry, scared and humiliated. He withdraws from Rémi, blanks him in the playground, goes in for macho ice hockey. Rémi is deeply baffled and wounded; Léo can hardly bear Rémi’s mute and then not-mute reproach, and with being confronted with his own fickle dishonesty.

The story of Close is disturbing because, however wised-up teenagers probably are now about the language of relationships and LGBT issues, compared to the relative naivety of maybe 10 years ago, the breakup of an intense friendship is shocking. There is still none of the adult life experience to explain it away, and the end of a friendship is devastating in the way a romantic relationship isn’t. For Rémi, Léo’s sudden decision to break up with him has the same effect as his mother deciding to put him up for adoption, or the sun not coming up in the morning. It is a violent, unspeakably painful rupture that Rémi does not have the language to explain to himself. He is perhaps mature in ways that Léo is not. Perhaps he is outraged at what amounts to a disloyal capitulation to homophobia, or perhaps it is not a question of being mature: he is just upset, or more than upset. There’s no doubting the force of this drenchingly sad story.

Peter Bradshaw, Th Guardian, 1st March 2023.

‘Close’: Cannes Review.

Lukas Dhont’s |Grand Prix-winning picture is an intimate, quietly devastating study of childhood friendship between two boys.

The disintegration of a friendship between two boys on the cusp of adolescence in rural Belgium triggers a tragedy, in the quietly devastating sophomore picture by Lukas Dhont. A study of children confronted with the kind of grief that they have neither the maturity or the temperamental framework to fully understand is always going to be a powerful proposition, but the combination of knock out performances, in particular from newcomer Eden Dambrine as Léo, and direction of uncommon sensitivity from Dhont makes for a picture which is intimate in scope but which packs a considerable emotional wallop.

Dhont has already shown himself to be a gifted director of young actors with his debut, Girl, which screened in Cannes Un Certain Regard in 2018, where it won several prizes, including the Camera d’Or for best first film. His work on Close builds on this, capturing both the churning interior world of the central character, and the quicksilver shifts in playground status, the tensions that can smoulder or spark from a throwaway comment. The recent success of Colm Bairéad’s The Quiet Girl, a film which shares with Close a delicacy of approach and an empathetic embrace, suggests that there is a healthy audience appetite for sensitively handled films such as this one, which explore the uncomfortable edges of childhood. Mubi has acquired the title for multiple territories, including the UK and Ireland.

We meet Léo and his best friend Rémi (Gustav De Waele) at the end of what seems like an endless childhood summer. They fight off imaginary invaders; they sprint through fields of the chrysanthemums that Léo’s family grow on their flower farm; they sleep, tangled together on the same bed, breath and limbs intermingling. But although they don’t quite realise it, the summer, like this period of childhood, is coming to an end. The giddy tumbling orchestral motif of the early scenes gives way to more plaintive and uncertain tones – it’s no accident that Rémi plays the oboe, surely the saddest-sounding of all the woodwind instruments.

The two boys, as close as brothers, are starting a new school. Nervous, they cling together as they navigate the new social structures of secondary education. Their physical intimacy does not go unnoticed. Dhont doesn’t overstate this – it’s in a brief glance from another boy who notices when Rémi rests his head on Léo’s shoulder, an interrogation from the girls about whether they are “together”. It’s enough to spook Léo, to make him suddenly self-conscious of the closeness which was previously their unquestioned natural state. He starts to place distance between them, throwing himself into passionate discussions of football with the sporty kids, and taking up ice hockey. Deft handheld camerawork captures the way his eye is still drawn to his former best friend, now sitting in the Siberian fringes of the school yard with the other nerdy kids. But when Léo unilaterally cancels their long-standing arrangement to cycle to school together, Rémi breaks down.

Without revealing too much about the story, suffice to say Dhont elegantly uses the quotidian routines of a child’s school and after school routine to show how nothing and everything can change all at once; how finding the words to speak can be the hardest part of coping with feelings for many young boys. There’s one extraordinary scene towards the end of the film when Léo, sadness saturating him like ink on blotting paper, picks up a stick, as if he can somehow fight off his emotions. There’s a naivety and futility in the gesture, in the way that it evokes the war games played in happier times: it’s an utterly heartbreaking moment.

WENDY IDE, Screen Daily, 27 MAY 2022