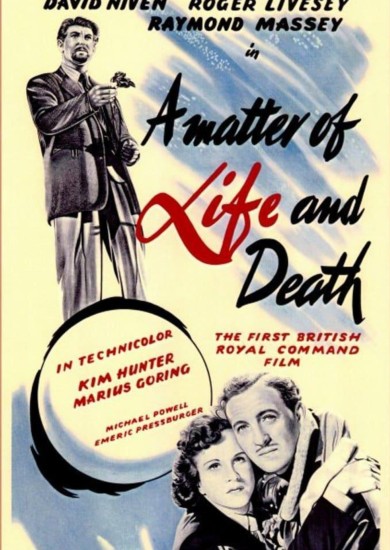

A Matter of Life and Death

A British WWII aviator who cheats death must argue for his life before a celestial court. This visually arresting Powell and Pressburger film stars David Niven.

Film Notes

THE SCREEN IN REVIEW; 'Stairway to Heaven,' a British Production at Park Avenue, Proves a Holiday Delight-- 'Humoresque' at Hollywood.

Had you harked you would have heard the herald angels singing an appropriate paean of joy over a wonderful new British picture, "Stairway to Heaven," which came to the Park Avenue Theatre yesterday. And if you will listen now to this reviewer you will hear that the delicate charm, the adult humor and visual virtuosity of this Michael Powell—Emeric Pressburger film render it indisputably the best of a batch of Christmas shows.

If you wished to be literal about it you might call it romantic fantasy with psychological tie-ins. But literally is not the way to take this deliciously sophisticated frolic in imagination's realm. For this is a fluid contemplation of a man's odd experiences in two worlds, one the world of the living and the other the world of his fantasies—which, in this particular instance, happens to be the great beyond. And the fact that the foreword advises, "any resemblance to any other worlds, known or unknown, is purely coincidental," is a cue to the nature and the mood.

We've no time for lengthy explanations—other than to remark that, by all the laws of probabilities, Squadron Leader Peter Carter should have been killed when he leaped from a burning bomber without a parachute over the Channel on May 2, 1945. And that is the natural assumption which revolves in the back of his injured mind. But, still alive after a freakish salvation and in love with a thoroughly mortal American Wac, he resists the hallucinary "messenger" who keeps summoning him to the beyond. Indeed, he resists so strongly—in his disordered mind, that is—that he conceives an illusory "trial" in heaven in which his appeal to remain on earth is heard before a highly heterogeneous tribunal. And through this court (and by a brain operation), he is spared.

That gives you a slight indication of the substance and flavor of this film—and we haven't space at this writing to give you any more, except to say that the wit and agility of the producers, who also wrote and directed the job, is given range through the picture in countless delightful ways: in the use, for instance, of Technicolor to photograph the earthly scenes and sepia in which to vision the hygienic regions of the Beyond (so that the heavenly "messenger," descending, is prompted to remark, "Ah, how one is starved for Technicolor up there!").We haven't space to credit the literate wit of the heavenly "trial" in which the right of an English flier to marry an American girl is discussed, with all the subtle ruminations of a cultivated English mind that it connotes, or the fine cinematic inventiveness and visual "touches" that sparkle throughout, notably in the exciting production designs of Alfred Junge.

Nor have we the space to say more than that David Niven is sensitive and real as the flier chap; that Roger Livesey is magnificent as his physician (and later advocate in the Beyond); that Kim Hunter is most appealing as his American sweetheart and that many more do extremely well, including Raymond Massey, who plays the lawyer for the Court of Records at the heavenly "trial." (Mr. Massey represents the spirit of the first Boston patriot killed in the Revolutionary War.)But we'll have much, more to say later, when we've got. Christmas out of our hair. Till then, take this recommendation; see "Stairway to Heaven." It's a delight!

Bosley Crowther, New York Times,

Stairway To Heaven (A Matter Of Life And Death)

“Stairway to Heaven" (1946) is one of the most audacious films ever made - in its grandiose vision, and in the cozy English way it's expressed. The movie, which is being revived at the Music Box in a restored Technicolor print of dazzling beauty, joins the continuing retrospective at the Film Center of 15 other films by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the most talented British filmmakers of the 1940s and 1950s.

"This is the universe," a voice says at the beginning of "Stairway to Heaven." "Big, isn't it?" The camera pans across the skies - but the story, as it develops, is both awesome and intimate, suggesting that a single tear shed for love might stop heaven in its tracks.

The story opens inside the cockpit of a British bomber going down in flames over England in the last days of World War II. The pilot, Peter (David Niven), establishes radio contact with a ground controller, an American named June (Kim Hunter). Peter is unflappable in the face of death, and an instant rapport springs up between the two disembodied voices ("I love you, June. You're life, and I'm leaving it"). Then Peter jumps out of the plane before it crashes.

What follows is a breathtaking pastoral moment, as the pilot, somehow alive, washes ashore and sees a young woman, far away, riding her bicycle home. It is, of course, June, and soon they are deeply in love. But there is a problem. Peter was not intended to live. Heaven has made an error, and an emissary, Heavenly Conductor 71 (Maurice Goring) is sent to fetch him back. Peter refuses to go, and a heavenly tribunal is convened to settle the case. This fantasy is grounded in reality by a brain operation the pilot must undergo; perhaps his heavenly trial is only a by-product of the anesthetic.

The British title of this film was "A Matter of Life and Death," and when the Americans retitled it "Stairway to Heaven," Powell wrote in his autobiography, he felt they had missed the point. But "Stairway to Heaven" may be a more expressive title, and certainly there is a stairway in the film, part of the incredible contribution of production designer Alfred Junge, who also provides one of the most spectacular shots in movie history, a view of heaven's underside: Vast holes in the sky with tiny people peering down over the edges. The heavenly scenes are shot in black and white, and the movie is filled with technical tricks, as when "real life" freezes while spirits leave their bodies.

The film's most audacious leap is to the trial in heaven to decide whether Peter will be allowed to stay on earth. Junge creates a heavenly amphitheater that fills the sky, and fills it with infinite ranks of heaven's population. Standing on one precipice, the prosecutor, an American played by Raymond Massey, argues against the British pilot. In one of the comic touches that deflates any excess profundity, he argues that Peter and June could never be happy together because they come from different cultures. First, we hear a radio broadcast of a cricket match; then an American big band broadcast. He asks the jury: "Should the swift current of her life be slowed to the crawl of a match of cricket?" But of course the question is not whether Peter and June will be happily married, but whether they will be married at all, and here the tear of love, captured on a rose petal by the Heavenly Conductor, becomes crucial evidence.

"Stairway to Heaven" has as its subtext the jockeying for power between Britain and America that took place after World War II.

British critics, at the time, sniffed that the film was too pro-American. What today's audiences will find amazing is the sheer energy of its invention. Powell and Pressburger (who always shared the writing, directing and producing credits, and whose production company was known as the "Archers") were not timid in reaching for new visual effects, and among the many startling sights in "Stairway to Heaven" is an eyeball's point-of-view of its eyelid closing, before the brain operation.

There's also sly humor. Heaven has a Coke machine for the arriving Yanks; newly appointed angels are seen carrying their wings under their arms in plastic dry-cleaner bags; the dialogue at the trial includes complaints like, "Would you repeat the question? It has `enamored' in it." Today's movies are infatuated with special effects, but often they're used to create the sight of things we can easily imagine: crashes, explosions, battles in space. The special effects in "Stairway to Heaven" show a universe that never existed until this movie was made, and the vision is breathtaking in its originality.

As a kid, Martin Scorsese discovered the Archers on TV, watching Million Dollar Movie on a New York station that would show the same film seven days in a row. He says that's how he did his homework. It's appropriate that the restoration of "Stairway to Heaven" and the revival of the other 15 Archers films (running at the Film Center through May) are "presented by Martin Scorsese."

Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times,

A Matter of Life and Death review – timely rerelease of sublime celestial romance.

Powell and Pressburger’s wartime drama, starring David Niven as an erroneously alive bomber pilot, is visually. extraordinary and politically topical.

A Matter of Life and Death is the utterly unique, enduringly rich and strange romantic fantasia from Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. You could put it in a double bill with It’s a Wonderful Life or The Wizard of Oz, though its pure English differentness would shine through. It was released in 1946, the same year that Winston Churchill coined the term “special relationship” – an idea that the film finds itself debating. With that concept now under pressure, 2017 is a good time for this classic to be rereleased in UK cinemas.

The film begins with a sensational flourish: a nuclear explosion that destroys a solar system. We start by drifting through outer space, accompanied by a droll narrative voice, commenting on its vastness and noticing a sudden supernova way in the distance: “Someone must have been messing about with the uranium atom.” The eerie casualness of that revelation sets the otherworldly tone for the rest of what follows. The starlit expanse, the intertitles, the distant detonation, the huge quasi-senatorial valhalla, all hint at where George Lucas got ideas for the Star Wars movies.

Then we find ourselves on Earth in 1945, where RAF pilot Peter Carter, played by David Niven, is flying back to Britain after a bombing raid, losing height, badly hit. He has presumably been attacking German cities, and it has to be noticed that Germans are not represented here, either in this world, or the next. Carter’s parachute has been damaged; he knows he is going to die, and with impossibly dashing flair, he radios his final position to an astonished American radio operator called June, played by Kim Hunter, asks her to contact his family and flirts with her. June and Peter fall in love at that moment.

The miracle is that Peter seems to survive, staggering out of the sea. He finds June, and with the help of a local doctor, Frank Reeves, played by the incomparable Powell/Pressburger stalwart Roger Livesey, he is gradually nursed back to health. Yet an emissary from heaven, in the form of a dandified pre-revolutionary French aristocrat played by Marius Goring, informs Peter that his survival is a mere clerical error and he is expected back in the afterlife right away. Peter complains that now he has fallen in love he is entitled to remain below. A huge trial is in prospect, and a prosecuting counsel is chosen: American revolutionary veteran Abraham Farlan (Raymond Massey), who intends to argue that this decadent Brit has no business with a good American girl. Frank believes that these heavenly visions are delusions caused by his brain injury and everything – or almost everything – is consistent with that rational explanation. But how did Peter survive the fall?

A Matter of Life and Death is a visually extraordinary film: a gorgeous artificiality is created by Alfred Junge’s production design and Jack Cardiff’s vivid Technicolor photography. Counterintuitively, the heaven scenes are in black and white and Earth is in colour. The modernist architecture of heaven is something to rival Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the “stairway to heaven” sequence (which gave this film its US title) is narcotically weird. Even down on Earth, and without the angelic visits, things have a distinct surreality. Frank likes nothing more than to keep the village under benign surveillance with his camera obscura device, evidently kept on a high rotating turret, which gives him live pictures of everything that’s happening in the village. He is like the voice and eye of an all-seeing God. And perhaps the most extraordinary moment comes when Peter encounters a naked young goatherd on the beach: it is this figure – like someone from a late Shakespeare play, such as The Tempest – who tells Peter that he is back on Earth. (The boy’s nakedness meant that this sequence was cut for TV transmission by prim US networks; Martin Scorsese has spoken entertainingly of his periodic exasperation at sitting down to watch and finding it is the bowdlerised version.)

So what does this film have to say about the special relationship? The speechifying on the subject of history and politics might disconcert some viewers who would rather hear and see more about Peter and June’s romantic adventure. But Powell and Pressburger are telling America and the world that just as Squadron Leader Peter Carter does not want go to heaven, so Britain itself is not dead; it does not deserve to be consigned to history along with those effete and irrelevant periwigged Frenchmen. Britain lives – in partnership with America.

I have watched this film many times, but it was only on sitting down to it again that I finally realised what Frank Reeves’s death reminded me of. Riding his motorbike fast in the rain, Dr Reeves had selflessly swerved in order to save the lives of the ambulancemen and their patient, conveying Peter to hospital. His sacrifice means that he can go to heaven to be Peter’s defending counsel. How should we feel about this terrible event? I had a flashback to a long-suppressed memory of reading CS Lewis’s The Last Battle, the final Narnia episode, in which Peter, Edmund, Lucy, Diggory and Polly are revealed to be killed in a train crash, along with the Pevensie parents, and so they can be admitted to eternal life. It was a profoundly strange happy-sad collision. So is this.

Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian, Fri 8 Dec 2017

What you thought about A Matter of Life and Death

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 (45%) | 8 (36%) | 4 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 22 Film Score (0-5): 4.27 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

63 members and guests attended this screening and we received a total number of responses of 22. This is a response rate of 35% and delivers a Film Score of 4.27

“I can't imagine that when the Film Society scheduled this that they can have dreamed that the self-sacrifice of a noble and principled young man for the freedom of his compatriots in the face of the myrmidon legions of a psychopathic demagogue would have such stark relevance. It does call certain things into question. How did those that suffered the Blitz view the cozily comforting image of the fallen happily receiving their wings in heaven? I loved this the first time saw it and every time since; the extraordinary opening sequence never fails to reduce me to tears. It is a perfect confection, delightful lightness of touch, gentle humour and exquisite playing disguising the weight of the matters under discussion ...at least until the court case which is always longer and more ponderously earnest than I remember. Beyond the plot and its concern for an Anglo-American understanding there is, as there always is with Powell and Pressburger, a raft of amusing and oddball detail: the benign Zeus-like Reeve's camera obscura with which he surveys his world with a caring eye, the classical Greek shepherd boy and the thundering Mosquito, the audience in heaven richly sprinkled with the less obvious contributors; the WRENs and Sikhs. The design is superb, a brutalist new-classical Heaven which Speer would have envied compared with a lush, Rococco Earth that would shame Fragonard. Transitions that Julian Temple must have studied. There is another P&P outing which makes an interesting comparison to this. 'A Canterbury Tale', shot during the war, is similar concerned with Anglo-American relations along with respect for our own history, love and faith. It does so in a considerably less melodramatic fashion but with huge warmth, the same quirky humour, stunning outdoors photography on the North Downs and has an even more moving finale. I'm not sure I don't prefer it”.

“It's an interesting premise and would be a good candidate for a remake. Some of the celestial realm scenery and special effects were impressively ahead of their time but I didn't find the performance of the two lovers very convincing. I really wanted to feel something deeper, especially with what's happening in Ukraine, but it just didn't get under my skin”.

“Wonderful to see this again! Thought that when this was released the special effects must have been marvellous, as well as filming celestial life in monochrome set against the striking colour of earth being deliberate showing wonder around now than in an unknown afterlife. If it was designed to celebrate the Anglo-American alliance perhaps we have a sharp metaphor questioning not only any ties between the Allies, as well Britain's status as a world power. Not many films released in 1946 would have shown how many countries the British Empire messed up, or how so many in USA still struggled. Clever script story splendid filming, sharp editing, intelligent camerawork, big set pieces & impressive performances. But with it being about love transcending life, death and the universe, also becomes about criticising the arrogance of victors throughout history. Enjoyed its political outspokenness, thread of British humour throughout – dry and colloquial and witty. Peter's death is foiled by a "pea souper" over the Channel, then his poke at Goring "Take that bit of Barley Sugar away". Thanks so much for showing this.”

“Very enjoyable, well-constructed film. Effects seemed good for 1946, especially the infinite escalator”.

“Very interesting; very cleverly done. Most entertaining”. “Very enjoyable”. “Would be very interested to know how received and rated when released “(CHECK THE WEBSITE FOR THE REVIEWS).

“A feast for the eyes! Wonderful film”. Great film and restoration”. “Excellent of its time”.

“Brilliantly filmed and so original. Was most entertained by the court hearing and the change of jury – all very clever and entertaining. David Niven - just so handsome”.

“An ambitious and highly imaginative take on a fascinating subject! (Why was the heavenly messenger so very ‘gay’?)”

“Interesting. Very much of its time”. “Original, even today. Quirky clever humorous, breath-taking”. “That was better than I expected”. “Great idea. Well done and original”. Very well done! Gripping”.