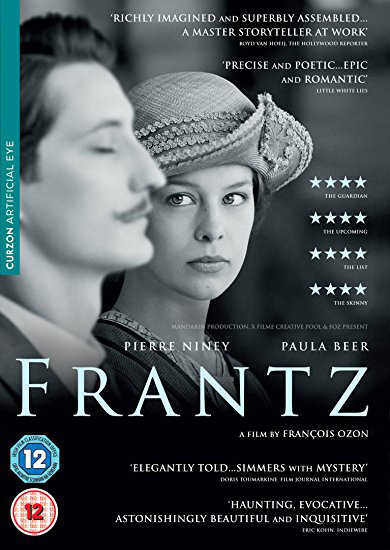

Frantz

In the aftermath of WWI, a young German grieving the death of her fiancé meets a mysterious Frenchman who arrives at the fiancé's grave to lay flowers. As a relationship develops, they both realize that neither has easy answers to the complex personal conflicts with each other and the dead man linking them. A melodrama with an unpredictable storyline.

Film Notes

There should really be a medical term for the head-spinning, brink-teetering sense of giddiness felt by film critics when they spot a reference to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. The feeling hits you with rippling regularity during Frantz, the new romantic mystery from François Ozon – although Ozon being Ozon, every riff and tribute is upside down, back to front, and bilingual to boot. Here the woman is in the James Stewart position at the apex of the love triangle, with her dead fiancé in one corner and a mysterious young man with some kind of connection to him in the other. It is every bit as handsome, teasing and therapeutically smart as we’ve come to expect from the prolific French director of Swimming Pool and Jeune & Jolie, although significantly less frisky than is standard. (His next film, Double Lover, which has its world premiere in Cannes later this month, looks likely to send the sap rising back to the usual bark-oozing levels.) Frantz’s Vertigo moments are so lovingly curated – there is even a pivotal scene in which the heroine quietly scours an art gallery for clues – that it comes as a surprise to learn in its closing credits that this film wasn’t initially prompted by Hitchcock at all (although his influence on the final film is undeniable). Instead, it was “freely inspired” by a little-known 1932 Ernst Lubitsch film called Broken Lullaby – although the suspenseful, enigmatic restructuring of its plot is all Ozon’s doing, as is its entire second half, which folds back on the first as sharply and neatly as a fingernail-stiffened crease, and throws its revelations into Rorschach-print relief. Frantz opens in Germany, 1919, in the picture-book town of Quedlinburg, where Anna (Paula Beer) is stoically carrying on with life while mourning her fiancé, who died in the First World War and after whom the film is named. Like Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca – another Hitch the film gets regularly snagged on – Frantz is dead before the story even starts, but his presence haunts everyone involved in it, not least of all his parents, Doctor and Mrs Hoffmeister (Ernst Stötzner and Marie Gruber), with whom Anna now lives as the daughter-in-law they almost had. Reports are circulating that a young Frenchman has been spotted laying flowers at Frantz’s grave. This is Adrien (Pierre Niney), who clearly has a good reason for being there, though when he’s first confronted by Anna in the churchyard, he keeps his cards clasped tight to his heart. Adrien is slender and birdlike, with a neat pencil moustache and a face that’s as easy to look at as it is hard to read: imagine a cross between Buster Keaton and David Hyde Pierce. And his story – that he and Frantz were friends in Paris, where they played violin and contemplated Manets in the Louvre – works as a salve on the Hoffmeisters’ broken hearts. Ozon has shot the film in austere black and white, but whenever Frantz’s memory flares up the frame flushes with colour, like lightly reddening cheeks. In the same way James Stewart in Vertigo groomed Kim Novak as a replacement for his lost love, Adrien starts to become a surrogate Frantz for Anna and the Hoffmeisters, while Philippe Rombi’s velvety, string-led score swells to Bernard Herrmann dimensions. He and Anna speak French together in private, just as she used to with Frantz – it was their “secret language”, she explains – and their chemistry is palpable, thanks to precise, captivating performances from Niney and Beer, who won the Marcello Mastroianni Award for emerging talent at last year’s Venice Film Festival. The burning question – is Adrien telling the whole truth about himself and Frantz? – is actually answered at the film’s halfway point (which was the climax of the Lubitsch film), after which the plot’s trail of cake crumbs leads Anna to France, and us in circles. Possibilities rear up then recede, then present themselves again in adjusted forms, sometimes so subtly you wonder as you watch if Ozon even meant it (of course he did). Even the tense interwar setting quietly leaves its mark on the story at hand, from the German townsfolk’s reservations over Adrien’s mere presence as a Frenchman and therefore recent enemy of the state, to a measured but implicative speech from Doctor Hoffmeister in the village pub about who bears responsibility for the death of his son and the many lost young souls like him. (The scene’s later mirror image features a rendition of La Marseillaise in a Paris cafe that reminds you of the savagery of that song’s familiar lyrics.) Frantz is the work of a rascal, but a rascal in an unusually reflective frame of mind. Even with its mysteries solved, you can’t help but keep turning it over.

Robbie Collin, The Telegraph, 12th May 2017.

François Ozon is nothing if not a restless film-maker. Despite his ridiculously prolific rate (he’s the Woody Allen of France, churning out one to two films a year), he seems adverse to ever being labelled an auteur. He’s tackled everything from a classic Gallic farce (Potiche), to a murder mystery (8 Women), to an erotic thriller (Swimming Pool), all with varying degrees of success. With an Ozon joint, you never quite know what you’re going to get. Yet still his latest comes as a big surprise. A largely black-and-white loose adaptation of the 1932 Ernst Lubitsch drama Broken Lullaby, which was in turn based on a play by French playwright Maurice Rostand, Frantz is also mostly told in German – a first for the director. It lacks the cheeky humour that characterised his three most inspired hits (8 Women, Potiche and Sitcom), instead favouring the mournful tone of his drama Under the Sand. Still, Frantz feels like new territory for Ozon. He radically shifts from the source material by imagining the entire second half of the story (which fittingly is the best part of the film). Vitally, Ozon has also changed the entire perspective to put a woman at the core of the tale. The original centered on a young Frenchman, who visits the titular German’s soldier’s grave after the end of the first world war. Frantz instead focuses on the German’s fiancee, who strikes up a quasi-romantic relationship with the mysterious stranger after he enters her life. Ozon is often at his best when working with women, and he has a fabulous talent in Paula Beer to bring his protagonist, Anna, to vivid life. She’s stunning in the role. When we first meet Anna, she’s understandably morose and quiet, having recently lost the love of her life to war. Her parents are eager to marry her off to another German suitor, but she’s unwilling to entertain the option. She perks up with the surprise arrival of Adrien (Pierre Niney), a lanky Frenchman with a sexy moustache, who claims to have been close friends with her late partner. Initially, her father wants nothing to do with the man (“Every French man is my son’s murderer,” he snarls). Adrien proves to be such a charming presence, however, that even Anna’s family soon come around to embracing him. Not long into Frantz, Ozon boldly shifts to full-blown colour for some key sequences. The flashbacks, recounting Adrien’s time spent with Frantz in Paris (they tour the Louvre; Adrien teaches Frantz how to play the violin), do away with the gloomy aesthetic, as does a lovely scene that sees Anna and Adrien grow closer over the course of a long hike in the mountains. The colour affords such needed respite from the misery that affects Anna’s circumstance, that when Ozon plunges back into darkness, it hurts. The Pleasantville-like approach is undeniably distracting, but its cumulative effect pays off profoundly in a final shot that’s too special to spoil. Ozon tends to favour a twisty narrative, and again offers a juicy one here that makes further plot description impossible. Suffice it to say that the film’s best stretch involves Anna journeying to Paris and take on a more active role as detective. It’s thrilling to watch such a sullen character finally take flight.

Nigel M Smith, The Guardian, 10th September 2016.

It’s a bold director who decides to remake an Ernst Lubitsch film, but François Ozon’s choice of “Broken Lullaby,” one of the master’s least known works and a drama to boot, probably seemed like a safe bet. This is the tale of a young Frenchman just after WWI, traveling to Germany to meet the parents and fiancée of a fallen soldier whom he says he knew in Paris, and it offers considerable emotional scope for Ozon’s pet themes, including the bounds of friendship and the idea of women coming into their own. Taken on these terms, “Frantz” plays like classic melodrama, and has certain charms. However, Lubitsch was invested in making an antiwar film with a romance attached, whereas Ozon reverses the order and tacks on a completely new second half. The results are oddly more artificial than the 1932 original, and considerably less moving. Sales however are likely to be brisk, not just in the home countries of France and Germany but further afield. That’s partly because “Broken Lullaby” – originally titled “The Man I Killed” – is largely forgotten, and partly because “Frantz” is the kind of semi-arty costumer that plays well everywhere (it is significantly better than Ozon’s previous costume pic, “Angel”). It could also benefit from the ongoing centenary commemorations of the Great War, providing a far different context from the one that greeted Lubitsch’s film, released just 14 years after the Armistice. The first half of “Frantz” is narratively faithful to “Broken Lullaby,” which starts in Germany in 1919; in the opening shot, Ozon fades from color to black-and-white, and thereafter reserves the polychromatic palette largely for prewar scenes. Anna (Paula Beer, “The Dark Valley”) lives in Quedlinburg with the parents of her dead fiancé Frantz (Anton von Lucke, in flashbacks). Joy is not a part of their lives since Frantz’s death one year earlier, and Anna remains with the kind couple, Dr. Hans Hoffmeister (Ernst Stötzner) and Magda (Marie Gruber), to look after them and mourn together. Anna is intrigued when she discovers that a Frenchman, Adrien (Pierre Niney, “Yves Saint-Laurent”) is visiting Frantz’s tomb, especially as defeated Germany is hardly welcoming toward French victors. She politely confronts him at the graveside, and the emotionally fragile young man tells her that he was a friend of Frantz’s in Paris before the war. Moved by this connection to her lost love, she introduces him to the Hoffmeisters, though the doctor at first brusquely resists having any contact with a Frenchman. Ozon picks up a remarkable number of scenes from “Broken Lullaby”: for example, one where Anna buys a dress for the first time since the war, in order to attend a town dance with Adrien. There’s also the sequence where Dr. Hoffmeister, now treating Adrien like a surrogate son, criticizes his Francophobe cronies, reminding them that while French soldiers may have killed their boys in the trenches, it was the German fathers, they themselves, who packed them off to battle. Sadly, Ozon is unable to match the wistful, understated magic of the dress scene, nor (by a long shot), the kick-in-the-gut potency of the antiwar tirade, which provided Lionel Barrymore with one of his finest moments on screen. In its latter half, “Frantz” departs completely from the source material (which Lubitsch took from Maurice Rostand’s play, “L’homme que j’ai tué”), with Adrien returning to France. Anna’s emotional investment in her dead fiancé has transferred itself to Adrien, and when a letter she sends is returned, she takes the train to Paris in search of the enigmatic man. Ozon is far more comfortable with these scenes, in which he deepens Anna’s inner tussle: no longer a dependent of the Hoffmeisters but retaining her attachment to their son, she’s on a journey to discover whether Adrien is a substitute for her dead lover, or the way toward a new future. Perhaps it’s not fair to constantly make comparisons, yet the choices Ozon makes force parallel assessments. For one, showing Frantz in flashbacks undercuts the potency of scenes in which his loved ones share his memory, especially as von Lucke has a soft, simpering quality that makes him far more suited to being paired with Adrien than Anna. The possibly homoerotic connection between the two men is never far from the surface, even though it’s not outwardly acknowledged. Lubitsch made his film as much about the parents as the Anna figure, which increased the sense of a gaping wound in all their lives; however when Ozon shifts to France, the Hoffmeisters are forgotten, and so too their grief, which Adrien was just beginning to assuage. Casting choices are also a problem, as Niney’s Adrien is neurotic yet too smooth, bordering on blankness. In contrast, Phillips Holmes, Lubitsch’s underrated actor, played the character on the edge of hysteria, his inescapable, haunted gaze a far more powerful expression of war trauma than Niney’s passively handsome eyes. Beer is far more a stand-out, and clearly Ozon finds her a more interesting character. Black-and-white is meant to ground “Frantz” in a fixed past, yet the reproduced monochromatic tones are obviously computer “corrected” from color, resulting in oddly flat visuals of little spatial interest. The color scenes work much better visually, especially as the palette chosen has the kind of genuinely older feeling that the black-and-white presumably strives, but fails, to meet. If monochrome is meant to convey something of the mournful quality of Europe at the time, it’s odd that Ozon shoots a trench scene – a very unnecessary trench scene – in color. Philippe Rombi’s score borrows heavily from Mahler in the first sections, intrusively aiming to enrich the emotions, leading to more Romantic orchestrations that fulfill the requirements of melodrama.

Jay Weissberg, Variety, SEPTEMBER 2, 2016

What you thought about Frantz

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 (56%) | 37 (36%) | 8 (8%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 104 Film Score (0-5): 4.46 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

142 members and guests attended this screening and 104 of you were sufficiently moved to provide a comment. This represents a hit rate of 73%. Although this is above our season average of 54%, it is still below the 79% response we had for Au Revoir Les Enfants last season. I have only been able to show a few comments here. They ran to three A4 sheets and all of them are on the website. Keep them coming. The most used words in your observations were, poignant beautiful and sad. “A lovely peaceful and moving film. Beautifully played”. “A sad tale – melancholy and almost coming of age – she learned to live again”. “A poignant tale. Anna hypnotic – beautifully acted”. Additionally many of you commented on the use of colour with the film proving to be “very atmospheric, moving and sad. Loved the use of b/w and colour to suit the mood”. Others commented on the subject with observations such as “the mirror image between the two halves in Germany and France worked well and the story was never quite what you expected. Not sure I got the ending - why was it in colour when that was the flashback mode? - had she committed suicide? Why couldn't she tell Adrien she hadn't the heart to tell Frantz's parents the truth? Obviously a thought provoking film!”. Also a “cleverly constructed screenplay about a rarely examined time: post Armistice. Many red herrings and blind alleys to keep the suspense. Beautifully acted, great period detail. No problems with sound or subtitles, but projector needs to be brighter”. And “I enjoyed this film very much. As it developed I wondered at first if Adrien Rivoire and Anna's fiancée had been in a gay relationship which seemed to be suggested to some extent by the description and subject matter of the Manet paintings and the intimate nature of the violin lessons. This would have been an interesting story line but I imagine was probably not possible bearing in mind the play it was based upon was written in 1932. I guessed soon that Adrien was the man responsible for his death who had come to seek forgiveness”. “This was a terrific film. There was so much to like about it from the very real and credible characters to the skill of Ozon in bringing the massive horror of war into the intimate, personal consequences of individual actions. Acting was controlled but superb and the photography spot on. I loved every minute despite the sometimes difficult to read subtitles. I must now find that painting”. “A little slow and sombre especially in the first half, albeit intriguing. I enjoyed it more as the film developed and the character of Anna in particular became more interesting. The acting was good, especially Anna, and though I wasn't sure to start with I came to appreciate the understated performances by the Hoffmeisters”. “My favourite film this season. A moving story of confusion of war, confusion and promise of life beyond the madness of killing. Very good Screenplay, filming and acting”. “I felt it was a bit stylised with the two mirrored stories in France and Germany, more interested in the pattern than the emotion. The German couple, the Hoffmeisters were outstanding and I really felt for them, but I found Anna rather cold and reserved so ultimately not involving. Hitchcock references rather passed me by. But I did enjoy the picture of German and French life after the war”. “I would rate this film as excellent. I thought it was a thoughtful portrayal of the effects of war on the personal lives of those involved. It was beautifully shot with a luminous central performance by Paula Beer”. “Both my husband and I felt that Anna was very fortunate to trace Adrien so quickly when she visited Paris and it was quite a twist in the tale that he was now going to marry another lady, albeit a marriage probably engineered by his mother. The choice of black and white for the majority of the film was also clever and emphasised the futility and bleakness of war. The change to colour at the end was reminiscent of the German television Heimat series of the 1970s”. “I thought that one weak point was the failure of Anna to tell her parents-in-law about Adrien's admission. This could not have been kept a secret had their romance blossomed and marriage followed. I wondered indeed if the father realised at their initial meeting but could not face the truth”. “My overall impression was that it was a film which emphasised the ultimate futility of war and how we are basically all humans with the same need for love, fear and guilt over our actions. I think its message is very prescient in these times of nationalism and borders. I am also involved in a World War I newspaper project and it reminded me very much of the deaths I have read about and that these horrors applied equally to both sides of the conflict”. “Somehow this was not as good as I thought it could have been – the first half for me worked better than the second. Paula Beer was excellent – Pierre Niney less impressive. Some entrancing scenes but overall a bit too long and languorous, without a real sense of what Germany and France were like so soon after the end of the War. And subtitles 1/3rd illegible…” “Beautiful, sensitive film with an interesting story line but so sad and a bit too convoluted – a rollercoaster of emotions! Some lovely music but perhaps over-long. Usual problem with subtitles! (Note: This was written last night – if done today might have been less positive.)”. “For quite different reasons from Housekeeping, whose range of comments is a fascinating insight into the diversity of our audience’s perceptions? In Frantz, I particularly liked what I think is called cinematography – the structuring of the visual images; an example is the shot of Anna from behind when she sits alone looking out over the lake – with a space beside her. Anti-war propaganda is always good, and a complicated love story that all probably works out for the best, but leaving us wondering how on earth the alternative would have worked out. Shame about the sub-titles (sorry to be boring about this, but there we are), at least some of us can cope some of the time (German O-level, failed)”. “Superb acting, clever twists, a love story with an anti-war message. We liked the use of black and white and colour and the music”. “Excellent. A very moving film. It illustrates well the tragedy of war. Upsetting to know that so soon after this Europe was at war again”. “Loved it”. “Beautifully acted. Such intensity of the pain of the young man killing another young man”. “A beautiful film. The historical background was perfect.” “Very good. I enjoyed this very much. The themes of the futility of war and forgiveness were treated very well. Great plot…I could not predict any of it”. “Beautifully done – but how frustrating!” “Wonderful bringing to life of coming to terms with the true horrors of War”. “An intelligent film – beautifully made – much to think about. A French man in Germany/German woman in France …” “A brilliant, atmospheric but incredibly sad film”. “So very good, moving and reflective. I could watch it again and again. A superb movie”. “A gentle and slow moving story – totally convincing and brilliantly acted. Very moving”. “Enjoyed the change from b/w to colour – and glad that Anna ended in colour! She deserved to after the sadness everyone was wrapped up in”. “A beautiful film. Despite …being far-fetched in terms of plot the acting made it believable”. “Beautiful. Strong performance from Paula Beer – full of emotion – couldn’t have predicted the ending”. “Loved it”. “Spellbinding”. “Exquisite film – so sensitive and powerful too!!” “Beautifully calm film which allowed reflection and appreciation without dragging. The music and the b/w added to the effect, though the shot of colour at the end was a little clunky”. “A riveting story, beautifully filmed. I liked the lack of colour and the subtle way it occasionally re appeared. Every single shot of the film was spellbinding. Interesting to show how both sides suffering this and really all wars”. “I loved how the parts in Germany and France mirrored each other. Loved how the ending was not the expected”. “An interesting remembrance of the life after the Great War. The screenplay captures the emotions of loss and the lives destroyed. Beautiful European scenery of where the filming was located. The contrast of the Germans and the French after the war, emotions running high – lest we forget – NEVER. Would appreciate better subtitles being accurate and clearer”. “Predictable that Adrien (Pierre Niney) would be the killer but otherwise unpredictable and an interesting take on WW1 – and war generally”. “Once again struggled with the subtitles but was still drawn into the web. A little slow in places and did not get the relevance of the colour during the swimming scene”. “A lovely film to ponder over the coming days. Their relationship, what is was based on and the two sides of war”. “The futility of war explored very passionately. Does it excuse bending the truth to prevent pain?” “Very stylish. Loved all the hats!” “Too dark to see the film at its best”.