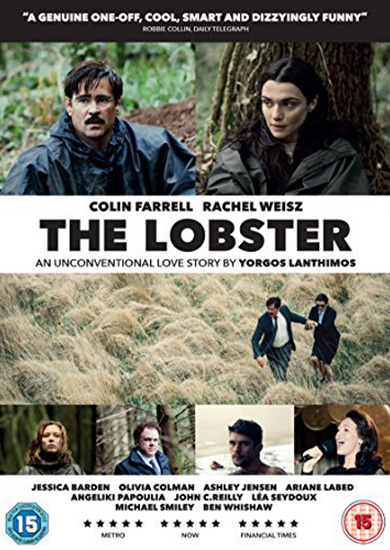

The Lobster

In a dystopian near future, single people, according to the laws of The City, are taken to The Hotel, where they are obliged to find a romantic partner in forty-five days or are transformed into beasts and sent off into The Woods.

Film Notes

The Greek filmmaker Yorgos Lanthimos is a deadpan dystopian comedian, an inventor of absurd, highly regulated societies that seem to exist in hidden pockets of everyday reality. In his 2010 film, “Dogtooth,” a middle-class couple raises three children according to an elaborate set of codes and rituals that include assigning new meanings to common words. In “Alps” (2012), members of a cult like organization impersonate the recently deceased for the benefit of the bereaved. And now, in “The Lobster,” Mr. Lanthimos’s first English-language feature — and, perhaps, his masterpiece thus far — guests at a grand, old-fashioned hotel are given 45 days to find love or face being turned into animals. That sounds like fairy-tale witchcraft, but there is nothing especially magical about “The Lobster.” (The title refers to the creature that the main character would choose to become.) It’s an aggressively literal-minded movie, set in a world where metaphors are all but banished and dreams and fantasies are drab and desperate affairs. The patrons of the hotel would be ridiculous if they were not so miserable, and vice versa. They are, in every sense, disenchanted. David (Colin Farrell), who has a hangdog expression and an actual dog at his side, is sent to the hotel soon after his divorce. His arrival provides an opportunity for the audience to be initiated into some basic rules and axioms of the movie’s universe, although Mr. Lanthimos (who wrote the script with Efthymis Filippou) keeps a few surprises in store for later. In the city from which hotel residents are exiled, marriage (straight or gay) is not just a sacrament but also an obligation enforced by the police. Happiness appears to be a state of dead-eyed consumerist ease illuminated by an occasional wan flicker of mirth or dread. At the hotel, the regimen of meals and activities is fairly straightforward. Behaviours are closely monitored, transgressions (notably masturbation) are punished, and desultory sexual relief is provided by the staff (notably a maid played by Ariane Labed). David soon befriends two other men (Ben Whishaw and John C. Reilly). They survey their prospects and applaud the formation of new couples. The main form of organized recreation is hunting for the “loners” who live in the woods beyond the hotel grounds. A guest who shoots a loner with a tranquilizer dart is rewarded with an extension — an extra day to pursue courtship and postpone beasthood. Plausible couples need to have one salient trait in common, like poor eyesight, susceptibility to nosebleeds or a sociopathic disregard for the well-being of others. Whether such compatibility can be faked is a central dramatic question. David and Mr. Whishaw’s character both try, with varying degrees of success. Mr. Reilly’s has a harder time. Out in the woods, the loners practice guerrilla warfare and declare their opposition to the sexual regulation and tyrannical monogamy represented by the hotel. Their leader (Léa Seydoux) tells new recruits that they can masturbate whenever they want. But as is so often true of revolutionary movements, this army of freedom fighters mirrors the dominant society in its capacity for brutality and coercion. Any kind of romantic or erotic attachment is forbidden, and disciplinary methods range from comical to horrific. Cruelty and humour are nestled like spoons in a drawer. Mr. Lanthimos’s method is to elicit an appreciative chuckle followed by a gasp of shock, and to deliver violence and whimsy in the same even tone. “The Lobster” is often startlingly funny in the way it proposes its surreal conceits, and then upsettingly grim in the way it follows through on them. It’s not quite that suicide, mutilation and murder are treated as jokes, but more that the boundary between the serious and the silly has been almost entirely erased. It falls to the actors to endow the director’s acute, misanthropic vision with emotional gravity and grace. Mr. Farrell, a habitual over-actor, is especially affecting because you can sense his effort to restrain himself. Rachel Weisz, as a loner who may be David’s soul mate, is perfectly cast as the only person in this world with the normal capacities for warmth, empathy and desire. She allows a credible love story to peek out through the elaborate trappings of allegory and satire. Those are interesting too, though. “The Lobster” could be thought of as an examination of the state of human affections in the age of the dating app, a critique of the way relationships are now so often reduced to the superficial matching of interests and types. It is also, more deeply, a protest against the standardization of feeling, the widespread attempts — scientific, governmental, commercial and educational — to manage matters of the heart according to rational principles.

A.O. SCOTT The New York Times MAY 12, 2016.

Yorgos Lanthimos has come to Cannes with another macabre adventure in black-comic absurdism: his first English-language feature. It’s an adventure which begins by being bizarre and hilarious but appears to run out of ideas at its mid-way point, and run out of interest in what had at first seemed to be its central comic image: humans turning into animals. The Lobster is a satire on the subject of our universal obsession with relationships, and our conviction that couplehood is the supreme expression of human happiness, a civilised institution which distinguishes us from the beasts. In a dystopian future, or strange alternative present, adults who are single, either through failure to find a partner or bereavement, must check into a hotel with other singles and find a genuinely compatible partner (the union’s authenticity has to be approved by the management) within 45 days, or they are transformed into an animal of their choice and released into the forest. But they can gain extra time for this “search” period with hunting trips into the forest with rifles and bringing down rebellious “singles” who have escaped into the wild there, living as singleton outlaws. Colin Farrell plays a sad lonely architect, recently dumped, who arrives at this deeply weird country house hotel - the stern manageress is played by Olivia Colman. He makes uneasy friends with other single guys, played by Ben Whishaw and John C. Reilly, and confesses to his new friends that he wants to turn into a lobster if things turn out badly: because they live for a long time and he has always loved the sea. It is brusquely pointed out to him that he is likely to meet a banal and horrible fate in a restaurant. They all have to participate in the activities: dancing and social interaction and conform to the strict no-masturbation rule. But Farrell is to glimpse the possibility of escape, and of living among the rebels in the forest in a society whose rules are hardly less dysfunctional and mad than those of the hotel. Here he is to fall in love with a beautiful, lonely woman played by Rachel Weisz and submit to rules imposed by charismatic, ruthless revolutionary played by Lea Seydoux. The Lobster is elegant and eccentric in Lanthimos’s familiar style: the world of the hotel is brilliantly created, and the film cleverly mocks the unexamined strangeness of hotels with all their corporate furniture of leisure and relaxation. This part of the film looks like the weekend break or team-building exercise from hell. It reminded me a little like Kinji Fukusaku’s survival nightmare Battle Royale or even Michael Anderson’s Logan’s Run, in which people face death by the age of 30. But once we leave the hotel for the forest, some of the film’s energy, atmosphere and control is dissipated: the superbly clenched, angular weirdness and explosive gags lose their direction and force and Lanthimos’s distinctive weirdness begins to look self-conscious and contrived. The audience is waiting for a climactic transformation scene, or non-transformation scene, or a scene which nails that fascinating and touching idea of a lobster and a lobster’s mysterious destiny. Here, there is disappointment. But there also dozens of astonishing and strange and funny moments of the sort that only Lanthimos can conjure.

Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian May 15 2015.

The Lobster is a European arthouse film par excellence – precisely the kind of project you can’t imagine ever being made in Hollywood. It has a Greek director (albeit one now based in the UK) and Irish, American and Dutch producers. Its actors are from all over the place. Its budget has been clawed together from innumerable different sources. This is an example of what used to be dismissed as a “Europudding” but it is also as rich and strange a film as you will see in a very long time – an absurdist tragi-comedy, performed in a very deadpan fashion. In the first sequence of the film, we see an assassination… of a donkey. Early on, it is as if we are watching a cross between Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and an episode of Fawlty Towers. David (Colin Farrell), a repressed, paunchy and now single man, has checked into a hotel. His task here is to find a mate. He has a set number of days to do so. If he fails, he will be turned into an animal of his own choosing. (His preference is for lobsters because they live for more than 100 years and are blue-blooded.) David has a sheepdog as companion. “He’s my brother. He was here a couple of years ago but he didn’t make it,” he blithely explains. The setting is the near future but the hotel, which is moderately luxurious, has a distinct whiff of the 1970s about it. It is a drab and oppressive place. Guests sit nervously alongside one another at breakfast, barely speaking. The manager (Olivia Colman) is very brisk and bossy in a Prunella Scales-like way. At hotel social events, she performs old pop songs in a dirge-like fashion. All the guests seem to have their own peculiar ailments or disabilities. Characters lisp (John C Reilly) or limp (Ben Whishaw) or have violent nose bleeds (Jessica Barden). One of the daytime recreations is for the guests to head out into the forests to hunt down “loners”. As the plot grows ever more far-fetched, the storytelling style remains grounded and understated. Farrell shows no emotion at all, whatever happens around him. There is the constant threat of violence. Guests who misbehave may be forced to put their hands into toasters or to wander around with boiled eggs under their armpits. “She jumped from the window of 180. There is blood and biscuits everywhere,” says one resident, reacting to a suicide as if someone has just spilled some food. This absolute lack of emotion is contrasted with the solemn music and the tremulous, melodramatic voiceover from Rachel Weisz as the “short-sighted woman”. Her character doesn’t appear on screen until well into the film but she is heard throughout. The screenplay, by the director, Yorgos Lanthimos, and his regular collaborator Efthimis Filippou, portrays a world in which anyone who is not in a couple is considered to be a pariah, on the level of an animal. Characters go to extreme lengths to prove their compatibility with potential mates. What they don’t convey in any way at all is pleasure in each other’s company or even sexual desire. They are all desperate to conform. The Maid (Ariane Labed, recently seen as the star of Fidelio, Alice’s Journey) is as much a coquette as she is a cleaner. Part of her job is to try to arouse the male guests. In one typically perverse scene, we see her testing out David’s virility. The camera cuts away to David’s dog, which looks as bored as he does. What makes The Lobster such an unusual and original film is also what is most likely to discomfit audiences about it. Lanthimos’s directorial approach is enigmatic in the extreme. He never lets us know whether any given scene is intended to be comic, grotesque or sinister – or a mix of the three. He deliberately blurs the lines between farce, thriller and dystopian horror. His protagonists seem so detached that it is hard for us to feel very much for them, at least until the final reel, when Farrell’s character, besotted by Weisz’s myopic siren, finally begins to show some emotion. Farrell’s performance as the oppressed, Pooterish everyman is well judged, and a world away from his usual macho star turns in movies such as Miami Vice or Alexander. As David, he has put on weight and has a chunky, unflattering, Lord Lucan-like moustache. In one excruciating scene, in which he tries to take off his trousers while wearing handcuffs, he shows unexpectedly Chaplinesque clowning skills. In his low-key way, he also hints at the yearning, jealousy and despair of the character. In the second half of the film, the action moves away from the hotel to the surrounding woods, which are inhabited by anarchists and loners led by Léa Seydoux. Action sequences here are handled in a comic, surrealistic fashion which risks diminishing their impact. We are very aware of the references to other movies and plays. There are echoes here of everything from Ionesco to Luis Buñuel’s films and Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend, which likewise placed bourgeois characters in bizarre and horrific situations. The problem is that the layers of irony and the extreme stylisation get in the way of what eventually turns out to be a very primal love story. The Lobster is a movie in which, arguably, far too much has been thrown into the pot. Even so, you can’t help but admire its director’s idiosyncratic brilliance. Every year, dozens and dozens of new films are made about love and relationships. Most follow exactly the same pattern. The French critic Raymond Bellour once described Hollywood films as machines to create couples. “Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl,” is the formula repeated again and again in US movies. That’s why Lanthimos’ approach is so refreshing. His film is about couples, too, but it comes at its subject matter from an angle that no Hollywood film-maker would ever have dared taking

Geoffrey Macnab, Independent, 15 October 2015

What you thought about The Lobster

Film Responses

| Excellent | Good | Average | Poor | Very Poor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 (14%) | 19 (20%) | 24 (26%) | 21 (23%) | 16 (17%) |

|

Total Number of Responses: 93 Film Score (0-5): 2.91 |

||||

Collated Response Comments

The Lobster scored the lowest of the season so far. In fact a couple of members even invented a new category, “DIRE” and referencing the nationality of the director with “all Greek to me”. Others observed that “it’s not often I feel I have wasted an entire evening” and a couple felt the experience was “torture” and that “for the level of belief it required, it delivered very little”.” For another the film was “beyond silly” and for those of you with long memories, remarking that “this is probably the Holy Motors of this season.” For some it was “thought provoking but too cruel”, a “weird film, difficult to understand a theme, not interesting or stimulating” supported by “not just weird, unpleasant”; “was it the cinema of the absurd”, “interesting concept of partners v loners but over indulgent and plain daft most of the time” “an exercise in incomprehensible dystopia”. And from the serious film buff in our membership I particularly liked, “An Ealing Comedy whose cast have all failed the Voigt Kompf test.” (Check out Blade Runner). A couple of members wrote to us after the screening and I quote below observations that mirror many of the one/two lines that you handed in at the end of the evening. “I do like weird films, but this was perhaps on the limit. I didn't enjoy it all that much and found some of it quite repellent, but how can you give a film like that "average"? It was certainly thought provoking so I'll score it "good" but with reservations! Reservations being that it was not really very enjoyable or uplifting…. I don't agree with the reviewer’s view of the film. I didn't feel that it was so much a portrayal of a dystopia as an exploration of where society might end up if all the human attributes of compassion, love, honesty, even friendship etc. are relegated in favour of order, discipline, consumerism… Many of the practices in their society are the worst imaginable, e.g. Being turned into an animal after 45 days, darting loners, violent punishment, wanton killing and so on. But they are not offered as realistic - they are illustrative of how far things could go…… So, I saw it as a warning against undervaluing our humanity and succumbing to more material pressures. But if the message is that obscure, what influence can it have? (Unlike 1984 or Brave New World).” A final few observations were; “Painfully long”. “Well-acted, good story but not my kind of film”. “Very strange”. “Started well, probably the most cynical view of humanity I’ve seen but with lightness of touch- then became totally brutal- the Shostakovich was perfect”. Because of the effort you all put into your thoughts and responses I have collated them all and you may see this and them on the website. Keep the comments coming. “A chillingly bleak, Orwellian nightmare, powerful in its immediate impact but finally dehumanised –a world of cruelty and emotional terror. Skilfully done” “Rubbish”. “Clever, well-acted, self-consciously mysterious, but ultimately empty except for the portrayal of existential angst”. “A film of two halves-first promising; the second had no connection with the first”. “At times two gruesome to watch”. “A quite bizarre film with some comic lines and some shocking scenes. Lost its way a bit towards the end and left quite a few unanswered questions”. “Strangely compelling but weird”. “Reminded me of Lord of the flies and Animal farm”. “Somewhere between wired and bizarre. A triumph of obscurance over sense”. “A sad comment on the very worst of human nature/society Christianity”? “Too odd for me but superb acting”. “The idea of satirising the social pressures for relationships and the idea that such relationships should be based on superficially similar traits- the film only partly succeeds. Did like the outrageous dialogue”. “Interesting, horrific, hadn’t a clue what it was about so am glad to read the notes and now a lot of it makes sense-very clever”. “Disturbing, thought provoking and strange-but worth seeing”. “Intrigued but non plused by the end of the plot! Lovely music. Possibilities of the landscape rather neglected. Some fine actors didn’t really show their paces”. “Bizarre, challenging-finally gruesome! Not a film for relaxing quietly at home. Brilliant music! Find it difficult to establish just what the message the film maker was trying to present”. “No idea what it was about but enjoyed it in a weird way”. “Funny, Weird, captivating and surprising”. ”A.O. Scott says it all in the last five lines of his critique”. “Packed with surprises, visual and aural.” “Disturbing, worrying. Watchable only once. Excellent performances. Amusing elements. Nightmare quality”. “Just what I joined up for”. “Visceral and highly original.” “A film where you are dammed if you are desperate to be a couple and dammed if you want to remain single.” “A real look at today’s modern youth and their obsessions of partnership or a simple life.” “An extraordinary film of perfect logic and disconnections in dreams and nightmares. Wonderful music and scenery, surreal and lyrical. Brilliant black humour but some gratuitous cruelty. - Interesting that I saw no disclaimer about animals being hurt. And hotels will never feel safe again.” “What a peculiar delight. Where did that come from? Borges, Bunuel, Renoir, Jacques Tati?”. “An inverse Powell and Pressburger played by particularly unimaginative children. Real life requires sacrifices and is not necessarily where you’d expect to find it. Unexpectedly funny.” “I do like weird films, but this was perhaps on the limit. I didn't enjoy it all that much and found some of it quite repellent, but how can you give a film like that "average"? It was certainly thought provoking so I'll score it "good" but with reservations! Reservations being that it was not really very enjoyable or uplifting. It requires an essay to respond fully rather than a few lines, but I'll offer one line of thought. I don't agree with the reviewer’s view of the film. I didn't feel that it was so much a portrayal of a dystopia as an exploration of where society might end up if all the human attributes of compassion, love, honesty, even friendship etc. are relegated in favour of order, discipline, consumerism (the hotel facilities for instance). Many of the practices in their society are the worst imaginable, e.g. Being turned into an animal after 45 days, darting loners, violent punishment, wanton killing and so on. But they are not offered as realistic - they are illustrative of how far things could go. The point is that as all these practices become the 'norm' and ubiquitous, they become accepted as 'just how it is'. It is true of society now - capitalism and the importance of profit for instance are not seriously questioned as a basis for our society. No-one in the film really stood up and objected, there was no underground resistance as in 1984, not even discussion of how unacceptable things were. The hotel entertainment which everyone clapped enthusiastically indicated the acceptance of their status quo. David's "hang dog" manner was very accepting without question. He did leave the hotel eventually, but he didn't fight. He just accepted the alternative loner way. The slight love story at the end perhaps indicated that all was not lost. There was still a flicker of humanity. But then, accepting the 'norm' of couples needing to have a common disability, he put his own eyes out. Complete acceptance of that practice. Of course it didn't hang together, it wasn't meant to - it was meant to be illustrative. E.g. how come the loners were so well dressed all the time, how did they get food/shelter? So, I saw it as a warning against undervaluing our humanity and succumbing to more material pressures. But if the message is that obscure, what influence can it have? (Unlike 1984 or Brave New World).”